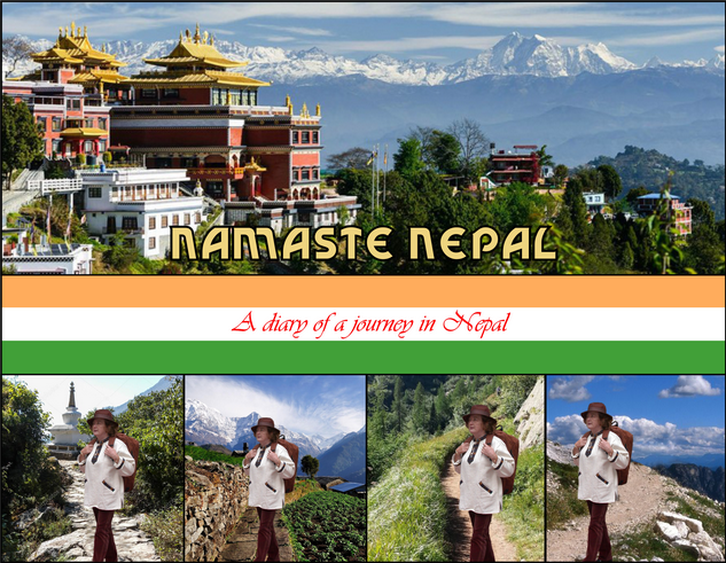

July 5th 9pm Kathmandu

At the airport, Ibrahim, Jane and I are accosted by a crowd of Nepalese who offer us hotels and guesthouses “clean and very cheap”. With great difficulty, we manage to rid ourselves of them, but only by agreeing to take one of their taxis. The bus, they tell us, has already gone at this hour. A guard, who may not have been entirely unbiased, endorsed this declaration ...

At the airport, Ibrahim, Jane and I are accosted by a crowd of Nepalese who offer us hotels and guesthouses “clean and very cheap”. With great difficulty, we manage to rid ourselves of them, but only by agreeing to take one of their taxis. The bus, they tell us, has already gone at this hour. A guard, who may not have been entirely unbiased, endorsed this declaration ... We arrive at the Marco Polo Guest House, which I had booked by letter from Italy. The owner, concerned, had already called the airport to find out why I had not yet arrived. Simple; the plane was two hours late, and that wasn’t all: our torch batteries had been seized and we had had a long walk around the airport to retrieve them. After the allocation of rooms, we go out to look for a restaurant. However, it’s past ten and everything is now completely closed. “I’m not really hungry”, I say to Jane, “I've had a plain dinner.”* However, Jane, who having declined the meal offered to us on the plane because she didn’t fancy it, consoles herself with some hazelnuts, the only edible thing available at this time.

We arrive at the Marco Polo Guest House, which I had booked by letter from Italy. The owner, concerned, had already called the airport to find out why I had not yet arrived. Simple; the plane was two hours late, and that wasn’t all: our torch batteries had been seized and we had had a long walk around the airport to retrieve them. After the allocation of rooms, we go out to look for a restaurant. However, it’s past ten and everything is now completely closed. “I’m not really hungry”, I say to Jane, “I've had a plain dinner.”* However, Jane, who having declined the meal offered to us on the plane because she didn’t fancy it, consoles herself with some hazelnuts, the only edible thing available at this time. * pun with plane

July 6th Bodnath

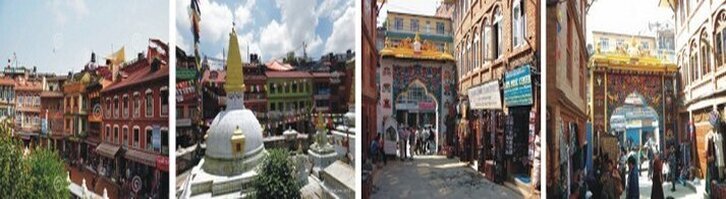

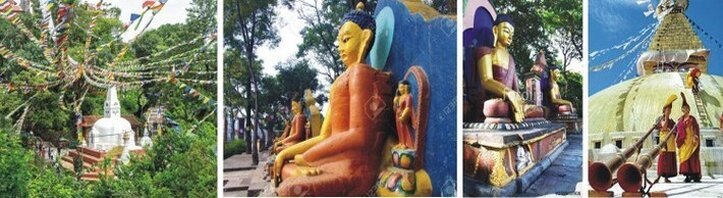

Today is the Dalai Lama’s birthday. It’s a must, therefore, to go to the Tibetan festival in Bodnath. I share a three wheeler with a Swede who lives in Rome and came to Nepal especially for this festival. We arrive there at nine, there are still few people around. I take this opportunity to climb the huge stupa. Meanwhile, I read the guide: "... The Bodnath stupa, 8 km from the centre of Katmandu, is the largest Buddhist shrine in Nepal. Originally built in the sixth century, its present state dates from the eleventh century. Placed at the culmination of three concentric octagonal terraces, the huge dome of whitewashed brick rises to 40 meters high, surmounted by a tower that on all four sides bears painted the immutable blue eyes of the serene Buddha.

Today is the Dalai Lama’s birthday. It’s a must, therefore, to go to the Tibetan festival in Bodnath. I share a three wheeler with a Swede who lives in Rome and came to Nepal especially for this festival. We arrive there at nine, there are still few people around. I take this opportunity to climb the huge stupa. Meanwhile, I read the guide: "... The Bodnath stupa, 8 km from the centre of Katmandu, is the largest Buddhist shrine in Nepal. Originally built in the sixth century, its present state dates from the eleventh century. Placed at the culmination of three concentric octagonal terraces, the huge dome of whitewashed brick rises to 40 meters high, surmounted by a tower that on all four sides bears painted the immutable blue eyes of the serene Buddha.

At the boundary wall there are hundreds of prayer wheels that the faithful spin during ritual circumambulation. The blinding white of the lime wash that covers the entire surface of the temple is often stained with orange saffron powder, which is thrown on the walls as a sign of devotion. The colourful prayer flags attached to the top await admission into heaven once faded and worn by the sun, wind and rain... "

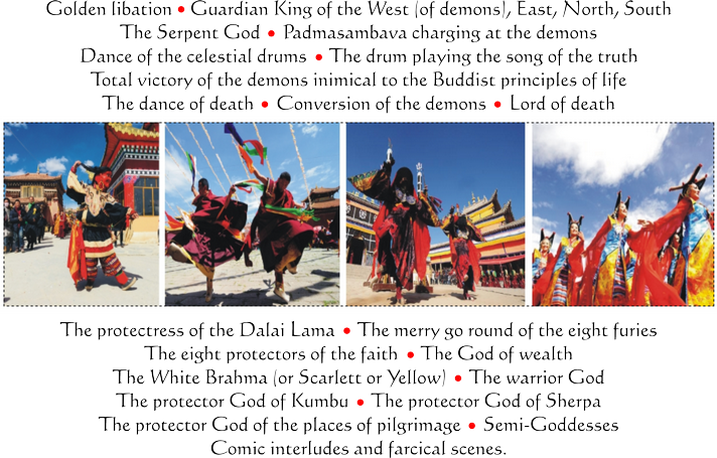

The space under the awning is now crowded and some of these Tibetans have walked for days to reach here. Behind a curtain there are some groups of dancers wearing traditional costumes. All I know about Buddhist dance are the titles from a text I read before leaving. Here they are:

Will these titles be sufficient to follow the dance? I somehow doubt it!

July 7th

Increasingly difficult! After the dances of yesterday, (beautiful choreography but the meaning is often indecipherable), today is the epic scene. From what I understand from the local guide, it’s a Nepalese version of the Mahabharata. Although the gist of this long poem has been explained to me, (the recital lasts more than 5 hours) I don’t manage to follow it. There are long monologues, that for those unfamiliar with Tibetan, don’t mean anything. The last straw is that in the audience there is someone from Turin who speaks Tibetan and consequently could enlighten me somewhat about the performance, but is too arrogant to do so.

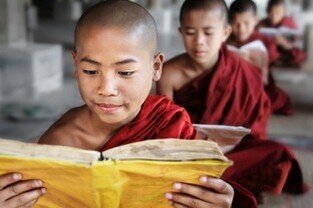

Increasingly difficult! After the dances of yesterday, (beautiful choreography but the meaning is often indecipherable), today is the epic scene. From what I understand from the local guide, it’s a Nepalese version of the Mahabharata. Although the gist of this long poem has been explained to me, (the recital lasts more than 5 hours) I don’t manage to follow it. There are long monologues, that for those unfamiliar with Tibetan, don’t mean anything. The last straw is that in the audience there is someone from Turin who speaks Tibetan and consequently could enlighten me somewhat about the performance, but is too arrogant to do so. Among the spectators there are also hundreds of Tibetan children squatting on the ground, remaining quiet for the whole five hours. Some people sleep despite the bustle of the crowd or what is happening on stage (which is very little, actually), but no-one leaves and teachers can chat in peace. Out of sheer masochism I try to imagine Italian children in their place ...

Among the spectators there are also hundreds of Tibetan children squatting on the ground, remaining quiet for the whole five hours. Some people sleep despite the bustle of the crowd or what is happening on stage (which is very little, actually), but no-one leaves and teachers can chat in peace. Out of sheer masochism I try to imagine Italian children in their place ... I am also more attracted by the spectacle offered by the people than that offered by the actors: I like these Tibetans very much, with their rosy cheeks and peasant looks, a bit rough but so happy and full of life! (Anyone who has found themselves in a crowd of Tibetans will understand!)

8th July Swayambhunath

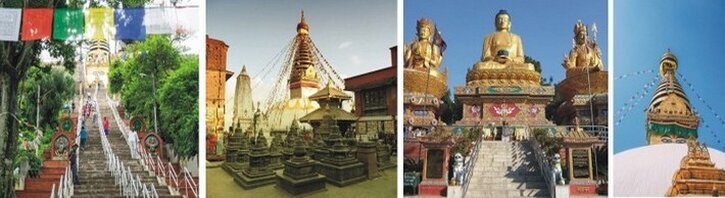

Today is the turn of Swayambu, the other large stupa near Kathmandu. It is 20 minutes by foot from Thamel. I saw it shining from on high above the green wooded hill on which it stands. The oldest in Nepal, it is the stupa of Adhi Buddha, the original Buddha, who appeared here in a lotus flame.

According to mythology, the temple was built to guard and protect the place where a small flame still burns. Its foundations date back to 2500 years ago, although its present form is from the fourteenth century.

The small sanctuary and the major part of the construction that crowns the hill were built between the 17th and 18th centuries. The steep stairs of the last section arrive right in front of the giant vajra, the thunderbolt of Indra and a Buddhist symbol of indestructible power. It is placed on a stone pedestal with twelve carved animals that represent the twelve months of the Tibetan year.

The terrace is covered with small votive temples, a pagoda and numerous statues, however, the large stupa covers the major part. A colossal statue of the Buddha marks the entrance.

Constructed from a dome of earth and bricks, the temple is crowned with a cube. Painted on the four bronze sides in red, white and black are the compassionate eyes of the Buddha, the third eye of wisdom and a nose in the form of the number one, the symbol of unity.

On each cardinal point there are the four niches of the Dhyani Buddha in meditation. The whole structure of the temple follows precise symbolic rules. Even here there is a line of prayer wheels and hundreds of votive lamps that consume hundreds of kilos of butter per day. There are also Hindu symbols in what is essentially a Buddhist complex. It is the first time I have seen this cultural mixture but I realise that there is more to come.

It is early and there are no tourists, the atmosphere is beautiful! There are men and women bringing their morning offerings and praying. They have come to ask a priest to celebrate the Puja. He is sitting on the floor in front of one of the lateral temples, equipped with rice, flowers, incense and a mysterious powder.....all the paraphernalia necessary for this occasion.  There is a man who is spraying saffron on the small Chaitya.

There is a man who is spraying saffron on the small Chaitya.

There is a man who is spraying saffron on the small Chaitya.

There is a man who is spraying saffron on the small Chaitya.His t-shirt reads “EAT DESSERT FIRST, LIFE IS UNCERTAIN!” a materialist phrase yet one of the most spiritual of actions!

Whilst I sit on the parapet enjoying the sun and the panorama, one of the hundreds of monkeys that live here moves up to me without my noticing.  I jump back afraid he might bite me. I have read that many of these monkeys are infected with rabies, something that will later be confirmed by a German Scientist, who is in Nepal to study their behaviour. He explained that the monkey attacked me because it had been provoked or badly treated in the past by someone else and had therefore become aggressive to all human beings.

I jump back afraid he might bite me. I have read that many of these monkeys are infected with rabies, something that will later be confirmed by a German Scientist, who is in Nepal to study their behaviour. He explained that the monkey attacked me because it had been provoked or badly treated in the past by someone else and had therefore become aggressive to all human beings.

I jump back afraid he might bite me. I have read that many of these monkeys are infected with rabies, something that will later be confirmed by a German Scientist, who is in Nepal to study their behaviour. He explained that the monkey attacked me because it had been provoked or badly treated in the past by someone else and had therefore become aggressive to all human beings.

I jump back afraid he might bite me. I have read that many of these monkeys are infected with rabies, something that will later be confirmed by a German Scientist, who is in Nepal to study their behaviour. He explained that the monkey attacked me because it had been provoked or badly treated in the past by someone else and had therefore become aggressive to all human beings. Returning from the stupa I am joined by two ‘well to do’ Milanese with a Nepalese guide. We take a short cut by crossing a wobbly bridge over the Vishnumati River whilst below us there are children and pigs splashing about in the mud.  After I leave them I am approached by a foreigner asking me for information. She is Italian and a sannyasin follower of Rajneesh. With a strong sing song Venetian accent she explains why she had decided some years ago to follow this guru and how happy she was with her choice. She is here to get her tourist visa. When we part I say that we would probably meet again, Katmandhu is small, Thamel is smaller.

After I leave them I am approached by a foreigner asking me for information. She is Italian and a sannyasin follower of Rajneesh. With a strong sing song Venetian accent she explains why she had decided some years ago to follow this guru and how happy she was with her choice. She is here to get her tourist visa. When we part I say that we would probably meet again, Katmandhu is small, Thamel is smaller.

After I leave them I am approached by a foreigner asking me for information. She is Italian and a sannyasin follower of Rajneesh. With a strong sing song Venetian accent she explains why she had decided some years ago to follow this guru and how happy she was with her choice. She is here to get her tourist visa. When we part I say that we would probably meet again, Katmandhu is small, Thamel is smaller.

After I leave them I am approached by a foreigner asking me for information. She is Italian and a sannyasin follower of Rajneesh. With a strong sing song Venetian accent she explains why she had decided some years ago to follow this guru and how happy she was with her choice. She is here to get her tourist visa. When we part I say that we would probably meet again, Katmandhu is small, Thamel is smaller.“If our karma permits it...” she replies.

Karma did not permit it; I never saw her again.

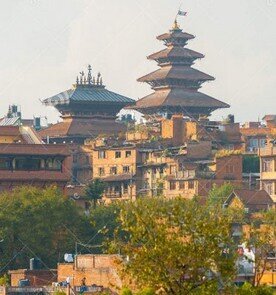

July 9th Bhagdaon or Bhaktapur

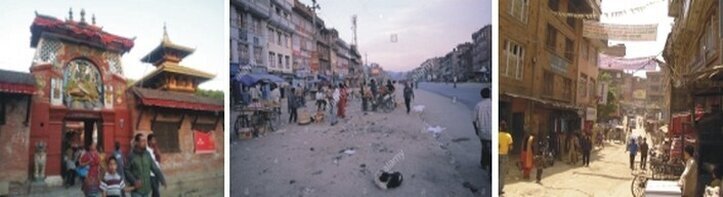

I hate the insufferable traffic and pollution of Katmandhu! By comparison the air we breathe in the most polluted European city is a breath of fresh air!

Part of my daily routine is to leave in the early morning for one of the smaller surrounding towns.

Today is the turn of Bhagdaon or Bhaktapur.

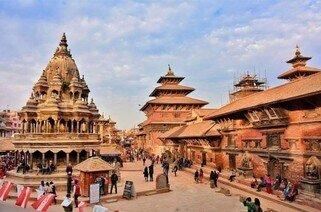

It is one of the Royal towns which competed with Katmandhu to be the capital city. You can get there by bus or tram and it takes about 20 minutes.

It is one of the Royal towns which competed with Katmandhu to be the capital city. You can get there by bus or tram and it takes about 20 minutes.According to mythology the city was founded by King Ananda Deva Malla, but in reality the squares with their temples and fountains were ancient villages that over the centuries grew and merged into one.

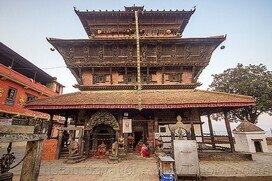

The original centre rose in the east in the area of the temple of Dhattatreya. However, when the town became the seat of the Malla and the capital of the entire valley between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, the building of new temples and palaces moved the centre westwood around Taumadi Tole.

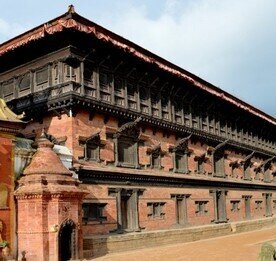

Durbar Square, the main square is flanked with temples and artworks. I like this square. In particular the wood cuttings by the Newari craftsmen. The palace of the 55 windows is a good example. Opposite this in the same square is the Golden Gate, a complex and elaborate carved work. There are the usual gods; Kali with eight arms and four heads, Garuda, Ganga, Jamuna, Hanuman, Narsingha, Narayan and many others.

Durbar Square, the main square is flanked with temples and artworks. I like this square. In particular the wood cuttings by the Newari craftsmen. The palace of the 55 windows is a good example. Opposite this in the same square is the Golden Gate, a complex and elaborate carved work. There are the usual gods; Kali with eight arms and four heads, Garuda, Ganga, Jamuna, Hanuman, Narsingha, Narayan and many others. In front of the Golden Gate on an enormous pedestal is the statue of the king Bhupatindra with his sword and turban which he offers in homage to Kali.Beside the pedestal rises the stone temple of Batsala Devi, home to the huge “bell of the barking dogs”. It is said that Ranjit Malla had it made so that it’s tone caused the dogs to howl and therefore scare away death from his palace. I ask around if this strategy works, but the response is negative.

Five minutes from Durbar Square is my favourite square. Here you find the temple of Nyatapola, a beautiful five storey pagoda. It is built on a high platform reached by a steep staircase flanked by pairs of guardians that encourage you to enter. In order from the top there are: the gods Baghini & Singhini, two griffons, two lions, two elephants and two wrestlers . Each figure is considered ten times more powerful than that immediately under it and the wrestlers are considered more powerful than any man. In this square there is also the temple of Bhairavnath which is rectangular in plan.

Five minutes from Durbar Square is my favourite square. Here you find the temple of Nyatapola, a beautiful five storey pagoda. It is built on a high platform reached by a steep staircase flanked by pairs of guardians that encourage you to enter. In order from the top there are: the gods Baghini & Singhini, two griffons, two lions, two elephants and two wrestlers . Each figure is considered ten times more powerful than that immediately under it and the wrestlers are considered more powerful than any man. In this square there is also the temple of Bhairavnath which is rectangular in plan. The reason I love this square however is not purely artistic. There was once a traditional temple in the form of a pagoda that had erotic carvings on the beams under the roof which has now been converted into a restaurant. From the balcony that runs around the whole building one can enjoy the magnificent view of the square. This became my favourite place for breakfast. One morning I watched the interesting way in which the waiter cleaned the glass table tops. First he spat generously on the table two or three times and then scrubed energetically with a rag that was in urgent need of cleaning itself. Who knows whether they clean the cutlery in the same way!

The reason I love this square however is not purely artistic. There was once a traditional temple in the form of a pagoda that had erotic carvings on the beams under the roof which has now been converted into a restaurant. From the balcony that runs around the whole building one can enjoy the magnificent view of the square. This became my favourite place for breakfast. One morning I watched the interesting way in which the waiter cleaned the glass table tops. First he spat generously on the table two or three times and then scrubed energetically with a rag that was in urgent need of cleaning itself. Who knows whether they clean the cutlery in the same way! Bhaktapur has remained my favourite place even after visiting many other beautiful and interesting places in my two month stay in Nepal.

July 9th 9am Katmandhu

Rain, rain and more rain!

I am sitting in the Marco Polo Hall. An ancient laundry woman is carrying on her back a huge bundle of tourist’s bedding and clothing to be washed. She is protected from the rain beating down on her by two plastic bags, one for her head and another much larger one for her clothes. A little while later an American woman, come to claim her clothes which are not dry due to the rain. She asks incredulously “ But ...you don’t have a spin dryer?” What innocence!

It is an ideal day for a visit to the library. I have just found out that the British Library is not far from my guest house and well supplied with books. This place I predicted would be where I would spend many hours, certainly on other rainy days like this one.

It is an ideal day for a visit to the library. I have just found out that the British Library is not far from my guest house and well supplied with books. This place I predicted would be where I would spend many hours, certainly on other rainy days like this one.Meanwhile I have to wait until 10 o’clock for the library to open. In the meantime I browse the publications in the hall. I find a leaflet entitled “Visitor’s Guide to Nepal, Printed by His Majesty’s Government of Nepal, Ministry of tourism”, there is a sentence that refers to the Pashupati Temple dedicated to Shiva:

“Entrance to the temple is permitted to the Hindus only” The word “permitted” is typed on a piece of paper and glued over the original word “restricted.” I imagine the poor Nepalese worker who patiently cut and pasted hundreds, no probably thousands of these words on all these leaflets.

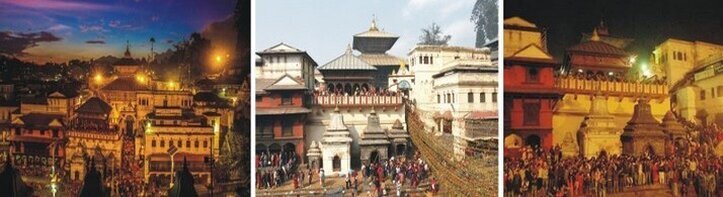

July 10th 9am Pashupati

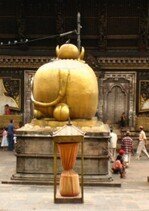

Unfortunately the word “permitted” in place of “restricted” has not changed anything for me. I cannot enter this beautiful temple and have to content myself with the giant hind quarters and other giant attributes displayed on the pedestal of the golden bull placed at the entrance.

Unfortunately the word “permitted” in place of “restricted” has not changed anything for me. I cannot enter this beautiful temple and have to content myself with the giant hind quarters and other giant attributes displayed on the pedestal of the golden bull placed at the entrance.One of the places in Pashupati that attracts me greatly is the “ghats”. Amongst other things they are an ideal place for meditation. I go in and sit down. Shortly after, the first two bodies arrive and they are prepared for the funeral pyre. Some cows come close and sniff the bodies, no one attempts to shoo them away. They are shortly followed by dogs and pigs. This is the beginning of the funeral ritual.

From the bridge overlooking the area men in western dress with a pretended air of elegance, throw large sacks of rubbish into the river. These men are obviously on their way to work, their wives having given them the rubbish on their way out of the house to get rid of it in some way. Given that there is no rubbish collection in the area they get rid of it by dumping it in the streets or in the river. The sacred Bagmati will take care of it!

July 13th Cycle ride

It’s Saturday and therefore a rest day. At first it is difficult to think of Saturday as a non working day but then it just becomes a habit. After a breakfast based on tea and bananas at 7.30 we leave.

Nima is the guide on this bicycle adventure. We start vigorously because I hope to escape the traffic before it becomes too busy.  This strategy is hopeless, however, because scarsely two kilometers into the journey there is a shattering explosion. A rear tyre has exploded! We return to the bike shop on foot to exchange the bike for another and set out again.

This strategy is hopeless, however, because scarsely two kilometers into the journey there is a shattering explosion. A rear tyre has exploded! We return to the bike shop on foot to exchange the bike for another and set out again.

This strategy is hopeless, however, because scarsely two kilometers into the journey there is a shattering explosion. A rear tyre has exploded! We return to the bike shop on foot to exchange the bike for another and set out again.

This strategy is hopeless, however, because scarsely two kilometers into the journey there is a shattering explosion. A rear tyre has exploded! We return to the bike shop on foot to exchange the bike for another and set out again. Stage one, Patan. At the Golden Temple I chat with the caretaker who also makes bronze Buddhas. He has been to Turin for business and is keen to recite all the places such as Porta Nuova, Porta Susa, Via Roma, Via Cernaia etc.

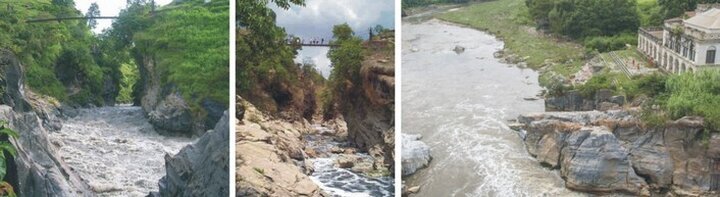

After this we head in the direction of Kirtipur, the city of the cut noses, but not before stopping to admire the Chobar Gorge on the way.

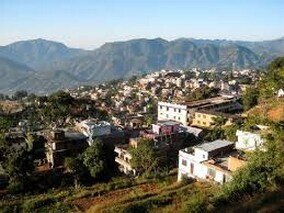

“Nestled on a hill 5km south west of Katmandhu, the medieval Newari fortress of Kirtipur was constructed by King Sada Siva Deva in the 12th Century. It was the stronghold that ruled over Gorkha. Pritvi Narayan Shah needed to attack this fortress in order to enter the valley and take the capital of the Malla kingdom. He besieged the fortress 3 times and it was only in 1768 that he finally succeeded. To vindicate his losses during these sieges he cut off the noses and lips of all the male occupants except one.

This was because of his love of music and the lucky one knew how to play a wind instrument. The evident signs of decay in the city are not linked entirely to this ancient defeat and its definitive eclipse as a flourishing and independent city, but also to the disastrous earthquake that occurred in 1934. Today Kirtipur appears as a neglected and melancholic city in a state of disrepair, its temples and beautiful houses with their triple wooden carved windows all in ruins.

During the day it is inhabited mainly by the old and children whilst the men and women are working in the fields or employed in traditional fabric making. In comparison with other places in the valley, however, it is more interesting because it has suffered less from tourism. Sitting in the shade along one of the dusty strips of road you can observe the life of a Newary town that has followed the same rhythm for centuries.”

After drinking a couple of sweet warm Fantas purchased from a shop located right in front of the temple of Bagh Bairav, the tiger god, one of the manifestations of Shiva, we climb to the pagoda dedicated to Uma and Maheshwar, the divine couple of Shiva and Parvati.

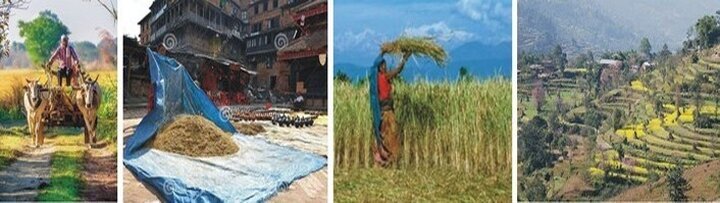

After drinking a couple of sweet warm Fantas purchased from a shop located right in front of the temple of Bagh Bairav, the tiger god, one of the manifestations of Shiva, we climb to the pagoda dedicated to Uma and Maheshwar, the divine couple of Shiva and Parvati. From here we admire the paddy fields spread out below us and Nima points out the peak of Langtang, where we will be going in a few days as guests of his relatives and of Gosainkund. Since his knowledge of architecture is no better than his knowledge of the mountains I take the lead and read:

From here we admire the paddy fields spread out below us and Nima points out the peak of Langtang, where we will be going in a few days as guests of his relatives and of Gosainkund. Since his knowledge of architecture is no better than his knowledge of the mountains I take the lead and read: “According to legend the temple of Hagh Bhairav was built in the 16th Century in the place where shepherds had jokingly moulded a clay tiger and later found it alive and with a full stomach due to it being on the sheep path. The temple is a pagoda built with four floors and three roofs supported by carved struts. From the central roof are hung shields, weapons and tools collected after the attack of Prithvi Narayan Shah on the fortress and offered to the gods by the devout. On the external walls of the ground floor there are some interesting frescos that show scenes from the Mahabharata in the late Malla style from the 16th century. They were however in a deplorable condition.

“According to legend the temple of Hagh Bhairav was built in the 16th Century in the place where shepherds had jokingly moulded a clay tiger and later found it alive and with a full stomach due to it being on the sheep path. The temple is a pagoda built with four floors and three roofs supported by carved struts. From the central roof are hung shields, weapons and tools collected after the attack of Prithvi Narayan Shah on the fortress and offered to the gods by the devout. On the external walls of the ground floor there are some interesting frescos that show scenes from the Mahabharata in the late Malla style from the 16th century. They were however in a deplorable condition.The Torana (a gateway) carved over the main entrance shows Vishnu riding Garuda and underneath it, Bhairav flanked by Ganesh and Kumar, the god of war”.

Earlier, whilst we were at Chobar Gorge, Nima had suggested going to Daksinkhali but I had refused. The idea of pedaling 20km uphill in this humidity whilst inhaling the exhaust fumes of the numerous buses carrying locals up to sacrifice goats and chickens did not appeal. However, since I feel full of energy and at this time of day I hope that the devout have all finished we return to the point where we had been this morning.

Whilst changing gear on my ancient mountain bike, (made in Taiwan) the chain comes off. My companion in misfortune fixes it and adjusts my gear mechanism in an instant. Now all I need is a puncture. Am I jinxed today?

The temple is located on the confluence of two rivers amongst the trees. It was built in the 17th century by Pratap Malla and is dedicated to the god Kali, here shown with 6 arms in the act of trampling Vetala with Ganesh.

I t is on this black stone sculpture that the blood of sacrificed animals is sprayed. The sacrificial animals are chickens, geese, goats, sheep and pigs. These animals must be ungelded males and dark in colour.

t is on this black stone sculpture that the blood of sacrificed animals is sprayed. The sacrificial animals are chickens, geese, goats, sheep and pigs. These animals must be ungelded males and dark in colour.

t is on this black stone sculpture that the blood of sacrificed animals is sprayed. The sacrificial animals are chickens, geese, goats, sheep and pigs. These animals must be ungelded males and dark in colour.

t is on this black stone sculpture that the blood of sacrificed animals is sprayed. The sacrificial animals are chickens, geese, goats, sheep and pigs. These animals must be ungelded males and dark in colour.After the rite of sacrifice the animals are returned to their owners who, after plucking or skinning them, hand them back to be cut up by the butchers who are there for that reason, put them in pans of boiling water and they are then eaten in situ. In fact, when we arrive we pass a family group of twenty or so who have with them a gas stove with a cylinder. The women are carrying large saucepans balanced precariously on their heads. In the meantime I wipe the sweat from my face and cleaning off some of the soot accumulated during the trip, I am bathed in the delicious perfume of the last sacrificial victim being cooked. If only someone would invite me to lunch!

But as no one picks up my unspoken wish, we sit in one of the tea-shops lining the road that climbs to the temple. A glass of milky tea, sweet and hot, is not exactly what I want at the moment. (I have tried a few times to ask for tea without sugar but they always look at me strangely!)

After having seen the slaughter of a dozen or so chickens and goats we leave at full speed down the mountain. I know that this will cost me at least a sore throat, but the pleasure of fresh air on my skin is too good to miss!

After having seen the slaughter of a dozen or so chickens and goats we leave at full speed down the mountain. I know that this will cost me at least a sore throat, but the pleasure of fresh air on my skin is too good to miss!Before arriving back at Kathmandu we take a turning to the right onto a dirt track that takes us towards a pretty village in the middle of brilliant green paddy fields. Soon, however, the road becomes impassable and we have to push our bikes. Even though we are only a few kilometres away from Kathmandu it seems light years away. Men and women are working in the fields, children running around and the oldies are playing Karen board in the shade of an ancient tree whilst a body is being burned on a pyre. All is quiet whilst life follows the rhythm of centuries, but for how much longer?

After passing through a wood we suddenly come out onto a tarmac road. We climb back on our bikes and head for Bodnath, our last destination for today.

After passing through a wood we suddenly come out onto a tarmac road. We climb back on our bikes and head for Bodnath, our last destination for today.We leave our bikes to visit one of the many monasteries that we find around the stupa. A group of child monks chant verses from a long narrow book that they unfold from the bottom to the top. Every now and again the sound of a horn cuts through the chanting. A monk passes and pours water over the heads of the boys, who try to move away and laugh.

We leave and head towards the temple; full of colour and like all Buddhist temples, contains a gigantic statue of Buddha. On our way out a palm reader offers to read my palm. I indicate that I am interested but do not have any money with me. He says he cannot read my palm without payment as this would bring bad luck. For me or more so for him?

14th July University

It is Sunday, a working day.

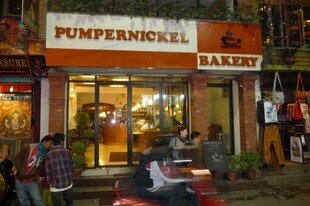

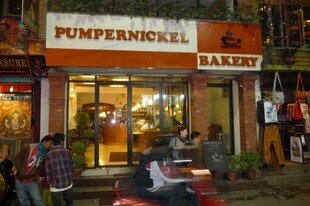

Two days ago I bought a large box of teabags because one of the boys that works at the guest house has invited me to breakfast with him.  So as not to burden his meager income I bring the tea, sugar and biscuits, he, the hot water. However this morning when I go down he tells me that the key to the room that contains the gas burner has been lost. So I go to Pumpernickel, a onetime tea and Austrian pastry shop that has sadly gone downhill.

So as not to burden his meager income I bring the tea, sugar and biscuits, he, the hot water. However this morning when I go down he tells me that the key to the room that contains the gas burner has been lost. So I go to Pumpernickel, a onetime tea and Austrian pastry shop that has sadly gone downhill.

So as not to burden his meager income I bring the tea, sugar and biscuits, he, the hot water. However this morning when I go down he tells me that the key to the room that contains the gas burner has been lost. So I go to Pumpernickel, a onetime tea and Austrian pastry shop that has sadly gone downhill.

So as not to burden his meager income I bring the tea, sugar and biscuits, he, the hot water. However this morning when I go down he tells me that the key to the room that contains the gas burner has been lost. So I go to Pumpernickel, a onetime tea and Austrian pastry shop that has sadly gone downhill.They tell me that they have lemon tea. I order some straight away as an alternative to the usual milk tea but it is a disappointment. I think it is made with freeze dried instant lemon flavoured tea. “Give me strength,” it means that tomorrow I will have to put up with sickly sweet milky tea again!

After talking to mum on the phone for a whole minute (150 Rupees) and after having woken her up (in Italy it is 4.30am), I go to the University with Dambar. He is an assistant in the physics department and to round off his life he also works at the guest house as a receptionist.

The bus that we take is so full that we are virtually hanging out of it. Up to this point I have only seen the locals doing this!

The University building is desolate inside. The library has never been dusted or the windows cleaned. Those that have been broken have not even been replaced. The physics hall reminds me of the dusty “scientific experimentation hall” of the Magistrale institute where I studied many years ago. The building inaugurated by the king at the end of the 60’s is located in the middle of a beautiful floral area.

The University building is desolate inside. The library has never been dusted or the windows cleaned. Those that have been broken have not even been replaced. The physics hall reminds me of the dusty “scientific experimentation hall” of the Magistrale institute where I studied many years ago. The building inaugurated by the king at the end of the 60’s is located in the middle of a beautiful floral area.The librarians offer me the chance to come back by myself and consult the books. At first this offer seems attractive, even though the procedure is somewhat complex, quite frankly excessively bureaucratic.  But then when I learn that each time I will have to fill in a form and leave my passport “as hostage” for as long as I am in the library, a shiver runs down my spine as Nepal has a flourishing market in stolen passports that fetch high sums on the black market. The Nepalese are amongst some of the most honest and upright people I have ever met but it seems stupid to leave my documents for all and sundry to get their hands on. When I ask where my passport would be kept I am met with the incredulous reply, “ Here, on the table naturally, where do you want me to put it?”

But then when I learn that each time I will have to fill in a form and leave my passport “as hostage” for as long as I am in the library, a shiver runs down my spine as Nepal has a flourishing market in stolen passports that fetch high sums on the black market. The Nepalese are amongst some of the most honest and upright people I have ever met but it seems stupid to leave my documents for all and sundry to get their hands on. When I ask where my passport would be kept I am met with the incredulous reply, “ Here, on the table naturally, where do you want me to put it?”

But then when I learn that each time I will have to fill in a form and leave my passport “as hostage” for as long as I am in the library, a shiver runs down my spine as Nepal has a flourishing market in stolen passports that fetch high sums on the black market. The Nepalese are amongst some of the most honest and upright people I have ever met but it seems stupid to leave my documents for all and sundry to get their hands on. When I ask where my passport would be kept I am met with the incredulous reply, “ Here, on the table naturally, where do you want me to put it?”

But then when I learn that each time I will have to fill in a form and leave my passport “as hostage” for as long as I am in the library, a shiver runs down my spine as Nepal has a flourishing market in stolen passports that fetch high sums on the black market. The Nepalese are amongst some of the most honest and upright people I have ever met but it seems stupid to leave my documents for all and sundry to get their hands on. When I ask where my passport would be kept I am met with the incredulous reply, “ Here, on the table naturally, where do you want me to put it?”This is an interesting side of the oriental mindset. For those who live in eternity, what value would you have for a passport in the greater scheme of things? Why worry so much? Now when you come in contact with this philosophy in the temples it is one thing, but in an office a degree of rationality is surely needed.

This inflexible rule regarding the passport means that I opt to use the British library, where, apart from having to leave my bag at the entrance, there are no other formalities. It is a great pity because I had seen some books on art and Nepalese religion that I would have gladly read.

Midday, return to hotel

I go back to Kathmandu under my own steam because Dambar has got lessons. I get off the bus at the wrong stop, start walking in the wrong direction, in fact…… I lose my patience and instead of going back on foot I take a three wheeler.

I go back to Kathmandu under my own steam because Dambar has got lessons. I get off the bus at the wrong stop, start walking in the wrong direction, in fact…… I lose my patience and instead of going back on foot I take a three wheeler.Lunch in my room: yak’s cheese, (good but so greasy!), sardines bought from the Swedish  supermarket for trekkers that I eat mushed up because the tin opener breaks straight away and I have to take my chances with what’s available, Malaysian rubra of dubious colour (on the label it says that it contains colouring and artificial flavours) and it has an even more dubious taste (why on earth did I buy it?), Nepalese rum and Hymalayan honey dissolved in hot water for my swollen throat.

supermarket for trekkers that I eat mushed up because the tin opener breaks straight away and I have to take my chances with what’s available, Malaysian rubra of dubious colour (on the label it says that it contains colouring and artificial flavours) and it has an even more dubious taste (why on earth did I buy it?), Nepalese rum and Hymalayan honey dissolved in hot water for my swollen throat.

supermarket for trekkers that I eat mushed up because the tin opener breaks straight away and I have to take my chances with what’s available, Malaysian rubra of dubious colour (on the label it says that it contains colouring and artificial flavours) and it has an even more dubious taste (why on earth did I buy it?), Nepalese rum and Hymalayan honey dissolved in hot water for my swollen throat.

supermarket for trekkers that I eat mushed up because the tin opener breaks straight away and I have to take my chances with what’s available, Malaysian rubra of dubious colour (on the label it says that it contains colouring and artificial flavours) and it has an even more dubious taste (why on earth did I buy it?), Nepalese rum and Hymalayan honey dissolved in hot water for my swollen throat.It was such an easy prediction of mine yesterday, whilst launching myself down the hill at Daksinkhali!

I’ll take an after lunch nap and then go with Sandra, also a guest at the Marco Polo,to meet Lilla, who sells jewelry in Durbar Square and (says Sandra) speaks perfect Italian.

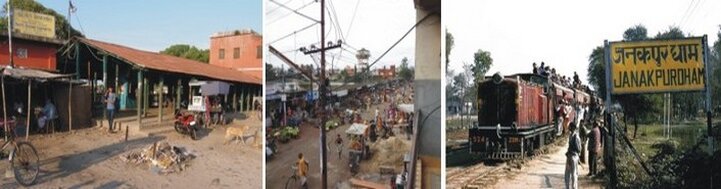

16th July on the way to Janakpur

I confess I was rather hesitant about travelling to Janakpur. Doubts based on the fact it being the monsoon season the condition of the roads is scary.

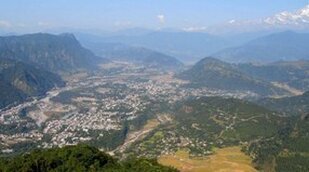

Janakpur is about 200km as the crow flies south east of Kathmandu, but to get there you have to cross half of Nepal. First you take the road to Pokhara to the west, then half way you change direction south to Terai, then you go east – a total journey of 12 hours. On the other hand, I do want to see a bit of the Nepalese plains – this is what tips the balance.

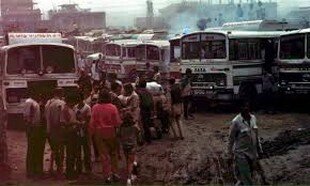

I find myself at the bus station at six in the morning even though the time on the ticket that I bought yesterday says 6.30. At 7 there is still no sign of the bus. We leave at 7.30 at speed. Maybe a tentative attempt to make up the lost hour?

I find myself at the bus station at six in the morning even though the time on the ticket that I bought yesterday says 6.30. At 7 there is still no sign of the bus. We leave at 7.30 at speed. Maybe a tentative attempt to make up the lost hour?Unfortunately we don’t get far – two hours later the bus breaks down and there is no hope of repairing it. After half an hour, the bus which was scheduled to leave Katmandu at 7 arrives.

I’m brought down to earth by the prospect of getting on this second bus. Buses in Nepal already travel packed to the gunnels without having to double the number of passengers. Besides there is still about 10 hours journey ahead of us and there is the unattractive idea of standing with my head bent because the roof of the bus is too low to allow me to stand straight, shaken by the continuous bumps from the uneven road surface and crushed by the crowd. Luckily my ticket from the broken down bus helps me to push my way through the crowd and to convince two Nepalese to share their seat with me. Since the seats in Nepalese buses are very small (their size!), I’m hanging off the edge of the seat, but it’s always better than standing.

I’m brought down to earth by the prospect of getting on this second bus. Buses in Nepal already travel packed to the gunnels without having to double the number of passengers. Besides there is still about 10 hours journey ahead of us and there is the unattractive idea of standing with my head bent because the roof of the bus is too low to allow me to stand straight, shaken by the continuous bumps from the uneven road surface and crushed by the crowd. Luckily my ticket from the broken down bus helps me to push my way through the crowd and to convince two Nepalese to share their seat with me. Since the seats in Nepalese buses are very small (their size!), I’m hanging off the edge of the seat, but it’s always better than standing.And what does it matter being uncomfortable, when you find yourself among people who are continuously showing their generosity and solidarity? It’s for this reason that I come to countries like this one – to rediscover these characteristics that no longer exists in our society – and I couldn’t care less about the discomfort, the hard life and food that is always the same.

I try to look out of the window but I don’t see much. It’s still pouring down and our progress is very slow through mud half a metre deep. We pass a very long column of soldiers marching, they do look miserable! There are road works along the whole of the road and we proceed at a snail’s pace; we often have to stop to let the oncoming construction lorries pass. Watching these road works it reminds me of the toils of Sisyphus, from classical legend. During the night, the monsoon rains destroy all the progress that has been made during the day.

I try to look out of the window but I don’t see much. It’s still pouring down and our progress is very slow through mud half a metre deep. We pass a very long column of soldiers marching, they do look miserable! There are road works along the whole of the road and we proceed at a snail’s pace; we often have to stop to let the oncoming construction lorries pass. Watching these road works it reminds me of the toils of Sisyphus, from classical legend. During the night, the monsoon rains destroy all the progress that has been made during the day.All the work is carried out by hand; axes, clubs, spades, picks, … they work in tandem with the spades; the man sinks the spade into the ground and the woman pulls the rope tied to the base of the handle to help him lift the weight of earth.

The road follows the Trisuli river where you can go rafting. I see groups of tourists with expensive equipment and ragged Nepalese who look after them in their role of ‘factotum’, (servant).

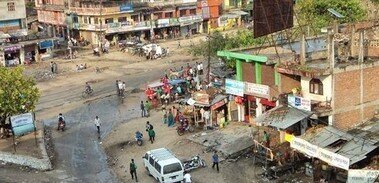

We stop at Mugling to eat. There are a dozen restaurants in the square and it is immediately obvious which ones are for ‘local people’ and which ones for tourists. Quite simply the latter ones have a certain ‘kitch’ air about them that is often the case with these kind of places for foreigners in poor counties when there hasn’t been much capital invested.

We stop at Mugling to eat. There are a dozen restaurants in the square and it is immediately obvious which ones are for ‘local people’ and which ones for tourists. Quite simply the latter ones have a certain ‘kitch’ air about them that is often the case with these kind of places for foreigners in poor counties when there hasn’t been much capital invested.  As the bus that I am on isn’t a tourist one but a normal service bus, with me being the only stranger, the driver directs us to one of the restaurants ‘for locals’. Who knows what his commission is for bringing passengers here, be it a free meal or something more?

As the bus that I am on isn’t a tourist one but a normal service bus, with me being the only stranger, the driver directs us to one of the restaurants ‘for locals’. Who knows what his commission is for bringing passengers here, be it a free meal or something more?I don’t eat; not because I don’t trust the food as is the case with lots of tourists in countries like this where hygiene isn’t exactly first rate and they find everything disgusting, but because I never eat when I’m travelling. As the stop is going to be for half an hour I go for a walk around the town.

It’s also due to the rain and the mud, but what squalor!

In front of a shack I see a hen and a cockerel with their feet tied together. The cockerel wants to go one way and the hen the other and they both tug at each other trying to free themselves from the knot that keeps them tied up. To me the animals symbolise marriage.

In front of a shack I see a hen and a cockerel with their feet tied together. The cockerel wants to go one way and the hen the other and they both tug at each other trying to free themselves from the knot that keeps them tied up. To me the animals symbolise marriage. A little further on, there is a pond with lots of geese swimming happily around. Their master arrives and calls to them. Flapping contentedly the geese assemble in single file and swim quickly towards him. Then they swiftly get out of the water, still in single file, and follow their master.

A little further on, there is a pond with lots of geese swimming happily around. Their master arrives and calls to them. Flapping contentedly the geese assemble in single file and swim quickly towards him. Then they swiftly get out of the water, still in single file, and follow their master.I go back to the square. Everyone has finished eating and so we get back on the bus and leave.

7 pm Janakpur

I love travelling alone but there are times when my enthusiasm wanes. I had read in the guide that Janakpur is ‘Indian in every respect except politically,’ but the looks and comments that I get between the bus station and my hotel give me a sense of unease and oppression. In Nepal it’s not normally like this.

I love travelling alone but there are times when my enthusiasm wanes. I had read in the guide that Janakpur is ‘Indian in every respect except politically,’ but the looks and comments that I get between the bus station and my hotel give me a sense of unease and oppression. In Nepal it’s not normally like this. Even the Welcome hotel suggested in the guide is Indian. It belongs to an Indian who lives a long way away, it was built by Indians, it is run by Indians and is full of Indians…

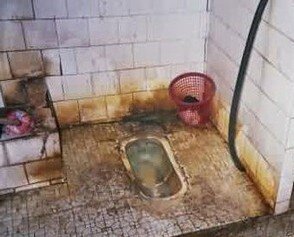

Already from the lobby on the ground floor there is a smell of urine that takes your breath away. I go up the stairs littered with every imaginable sort of rubbish and what with the encrusted walls and the dim light bulbs there is a nightmarish atmosphere.

They show me a few rooms: small, suffocating, with small high windows which resemble a medieval prison cell. I don’t suffer from claustrophobia but there is no way I’m going to be able to spend the night in a place like this.

And the prices too! Much more expensive than those indicated in the guide. In the end they show me the suite on the top floor for which they are asking an exorbitant price of 350 rupees. I’ll describe it: on the floor there are the remains of what was once linoleum, curling and bubbling and somewhat of a trap for the unfortunate occupant of the room; the furniture comprised of a small rickety table, a small fake leather sofa with sagging seats and springs sticking out, two beds with dirty sheets and finally the walls and ceiling as stained and encrusted as the stairway.

In the bathroom there are large brown marks everywhere; on the white wall tiles, on the bath tub and on the toilet, caused by the brown liquid which they call water. Beetles as big as walnuts appear and disappear through holes. I turn on the tap and then the shower and the same brown liquid that I see everywhere comes out. They say that there is a ‘shortage of water’ – the water that is coming out of the tap must be from the depths of the water tank - so why waste it in the bathroom? And a… ‘shortage of water’ in the wet season? But what if it’s tipping it down outside!

In the bathroom there are large brown marks everywhere; on the white wall tiles, on the bath tub and on the toilet, caused by the brown liquid which they call water. Beetles as big as walnuts appear and disappear through holes. I turn on the tap and then the shower and the same brown liquid that I see everywhere comes out. They say that there is a ‘shortage of water’ – the water that is coming out of the tap must be from the depths of the water tank - so why waste it in the bathroom? And a… ‘shortage of water’ in the wet season? But what if it’s tipping it down outside!I go down to reception to ask for a hand towel so I can clean my hands after having got them dirty from the water but they give me one that is so dirty that I don’t have the courage to use it. As there is a restaurant I order a pot of tea without milk and sugar. They bring me a glass of extremely sweet and milky tea that they have bought from one of the street tea sellers, reselling it to me for 5 times the price. Seeing as I can’t be bothered to make a fuss, I decide that from now on I won’t ask for anything else – I’ll pay the price asked for the room even if I think it is overpriced and I’ll go back to Katmandu tomorrow, although I had planned to stay a bit longer.

I go to bed with a certain sense of anguish; I hope that the drunken Indians who I had seen earlier drifting around on the terrace outside my room won’t be bothering me tonight. So that I don’t hear the brawl anymore I decide to use earplugs.

17th July Janaki Mandir

I wake, as usual, at dawn and I'm hungry. The last meal, apart from a few bananas eaten yesterday, was two days ago.

I wake, as usual, at dawn and I'm hungry. The last meal, apart from a few bananas eaten yesterday, was two days ago.I get dressed and I go out at six to find a restaurant. Since I don’t find one, I go into a tea room to at least have a cup of tea. I observe the original way in which the tea maker fills the glasses. He puts them all in a row then raises the pot to more than a meter high and pours the tea without stopping. In a niche between the various offerings to Shiva, I see light bulbs. Curious! I take a look at one and the filament has blown. I look at the others - the same thing. It seems to me the same practical principle of Daksinkhali: there you eat the meat that is first offered in sacrifice, here is the same deal with light bulbs; when no longer needed, they are offered to the deity. Nothing should be wasted!

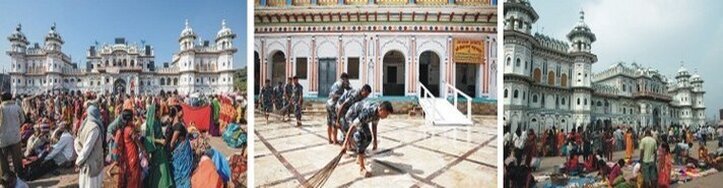

With my increasingly empty stomach, I visit the city. First stop, the temple. It is called Janaki Mandir and is the pilgrimage destination for Hindus.

It is dedicated to Sita, the beautiful princess, wife of Rama, celebrated in the Ramayana. It reminds me of those firework models that elementary school children make (or made) from cardboard tubes.

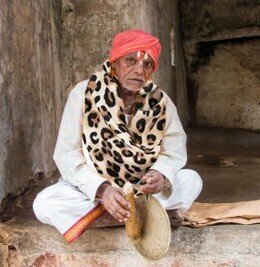

I stop for a while in the courtyard surrounding the temple to observe the incredible passing people. Meanwhile almost all the sadhus here have leopard print tunics -I don’t know why. Do they have some symbolic significance? Now a guy with a white Navy uniform goes by, with lots of braid. Where did he get it from? To complete the attire, or perhaps to demystify it, he has a golden chain mail bag hanging from his shoulder on a gold chain. Around his neck he wears a necklace made with those seeds, whose name escapes me now, that all the leading Indian sadhu or gurus wear.

I stop for a while in the courtyard surrounding the temple to observe the incredible passing people. Meanwhile almost all the sadhus here have leopard print tunics -I don’t know why. Do they have some symbolic significance? Now a guy with a white Navy uniform goes by, with lots of braid. Where did he get it from? To complete the attire, or perhaps to demystify it, he has a golden chain mail bag hanging from his shoulder on a gold chain. Around his neck he wears a necklace made with those seeds, whose name escapes me now, that all the leading Indian sadhu or gurus wear.Another curious type is now standing next to me and tells me something I do not understand. He is wearing a pink sari and is smoking. He has very long hair held back by a red band holding a long peacock feather high on his head. Since I do not understand what he says he starts to read a book of verses, half aloud, half chanting.

And now a family group arrives: the very small father carries his daughter, who is twice the size of him, on his shoulders while his wife is following with their household goods. Like Catholics take their incurably ill to Lourdes, evidently Hindus carry them here in the hope of a miracle.

And now a family group arrives: the very small father carries his daughter, who is twice the size of him, on his shoulders while his wife is following with their household goods. Like Catholics take their incurably ill to Lourdes, evidently Hindus carry them here in the hope of a miracle.

How many things in common different religions of the world have! We are here in Janakpur where there are many artisan silversmiths.

Whilst I’m in one of their shops a beautiful, tall, young Nepalese man approaches and addresses me. He is wearing glasses and has an intellectual air about him.  He is a pharmacist and has his shop on this same street. We go there because I am interested to see what kind of medicines are sold. Meanwhile, we chat and I ask him where he completed his studies. No studies, he says. He worked for two years in a practice run by another pharmacist, then opened the shop. I look at some of the boxes of medicines which are all imported from India but unfortunately they aren’t ayurvedic medicines or herbal remedies, but chemical ones. Moreover, they have all expired. I tell him this and he replies that he had been sold them at a lower price by the pharmacist who he worked for before. When you start a business, he adds, it all costs so much money! Sooner or later I’ll have to throw them out ...

He is a pharmacist and has his shop on this same street. We go there because I am interested to see what kind of medicines are sold. Meanwhile, we chat and I ask him where he completed his studies. No studies, he says. He worked for two years in a practice run by another pharmacist, then opened the shop. I look at some of the boxes of medicines which are all imported from India but unfortunately they aren’t ayurvedic medicines or herbal remedies, but chemical ones. Moreover, they have all expired. I tell him this and he replies that he had been sold them at a lower price by the pharmacist who he worked for before. When you start a business, he adds, it all costs so much money! Sooner or later I’ll have to throw them out ...

He is a pharmacist and has his shop on this same street. We go there because I am interested to see what kind of medicines are sold. Meanwhile, we chat and I ask him where he completed his studies. No studies, he says. He worked for two years in a practice run by another pharmacist, then opened the shop. I look at some of the boxes of medicines which are all imported from India but unfortunately they aren’t ayurvedic medicines or herbal remedies, but chemical ones. Moreover, they have all expired. I tell him this and he replies that he had been sold them at a lower price by the pharmacist who he worked for before. When you start a business, he adds, it all costs so much money! Sooner or later I’ll have to throw them out ...

He is a pharmacist and has his shop on this same street. We go there because I am interested to see what kind of medicines are sold. Meanwhile, we chat and I ask him where he completed his studies. No studies, he says. He worked for two years in a practice run by another pharmacist, then opened the shop. I look at some of the boxes of medicines which are all imported from India but unfortunately they aren’t ayurvedic medicines or herbal remedies, but chemical ones. Moreover, they have all expired. I tell him this and he replies that he had been sold them at a lower price by the pharmacist who he worked for before. When you start a business, he adds, it all costs so much money! Sooner or later I’ll have to throw them out ...Finally I come across a restaurant: it is Indian of course, and the waiter tells me that his family lives in Bihar and that every year he comes to work here for six months.

I order tandoori chicken, but when I get it, I realize that, more than anything else, it is tandoori bones! Fortunately, there are rice and vegetables to fill my stomach.

I order tandoori chicken, but when I get it, I realize that, more than anything else, it is tandoori bones! Fortunately, there are rice and vegetables to fill my stomach.

I note that on my table there is a bottle full of water, in which plastic flowers are immersed. What westerner would ever think to put artificial flowers in water?

I order tandoori chicken, but when I get it, I realize that, more than anything else, it is tandoori bones! Fortunately, there are rice and vegetables to fill my stomach.

I order tandoori chicken, but when I get it, I realize that, more than anything else, it is tandoori bones! Fortunately, there are rice and vegetables to fill my stomach.I note that on my table there is a bottle full of water, in which plastic flowers are immersed. What westerner would ever think to put artificial flowers in water?

July 18th: Return to Katmandu

Half an hour before it is due to leave, I'm already seated on the bus, which is filling up little by little. At a certain point, and when all the seats are taken, a Tibetan woman with a small baby boards. Seeing that no-one shows any sign of giving up their seat, I get up and signal to her to take my place. She accepts with a smile and once seated starts breast feeding the baby. She seems rather concerned, though, regarding the contents of a sack she has left in the gangway and she is quick to shoo away anyone who tries to sit on it.  She has told me she runs a shop so it's likely that she's come to Janakpur to stock up and the sack could well be full of such things as packets of crisps, pop-corn or other junk food of the kind which, alas, is becoming popular even here.

She has told me she runs a shop so it's likely that she's come to Janakpur to stock up and the sack could well be full of such things as packets of crisps, pop-corn or other junk food of the kind which, alas, is becoming popular even here.

She has told me she runs a shop so it's likely that she's come to Janakpur to stock up and the sack could well be full of such things as packets of crisps, pop-corn or other junk food of the kind which, alas, is becoming popular even here.

She has told me she runs a shop so it's likely that she's come to Janakpur to stock up and the sack could well be full of such things as packets of crisps, pop-corn or other junk food of the kind which, alas, is becoming popular even here.After we've been travelling for a couple of hours, we stop to take on huge sacks of Nepalese cucumbers. Judging by the huge effort it takes to heave these sacks up onto the roof of the bus,I guess they must weigh a total of several hundred kilos. “Let's hope the tyres are good and strong!” is the comment of one of my fellow passengers. I can't help thinking that in fact the bus is already packed to overflowing and considering the condition of the roads . . . . .

Unfortunately my fears prove not to be unfounded! Less than half an hour along the road one of the rear tyres literally explodes. Two or three men take advantage of this unscheduled stop to get out and go for a 'comfort stop' taking a torch with them. Not one of them stops to provide some light for the poor devil who has to change the wheel in the pouring rain and pitch darkness. I get off to provide some light and find I have to get into the most uncomfortable, twisted position in order to shine the torch beneath the bus to where the spare wheels are chained right in the middle under the floor of the bus.

The operation of releasing and fitting a spare wheel takes the best part of half an hour and by the time it's done I'm soaked to the skin. Unfortunately the tyres will deflate and have to be replaced four more times. Since we don't have so many spare tyres, we're obliged to stop twice at service stations to get the tyres mended on the spot. However, on these two occasions I merely hand my torch over to those involved without leaving the bus. Kindness is okay, but not at the cost of catching pneumonia.

Despite the dangers and being beset by accidents, this mainly nocturnal journey was wonderful; going through villages lit only by candlelight or oil lamps was like being in one of those Christmas crib scenes.

When we stop at Bardiwas, a very sick woman comes aboard; she is being taken to hospital in Katmandu. The youths and men around her are chain smoking showing no regard at all for this poor woman who can hardly breathe. By the way, I'd like to suggest that the saying “to smoke like a Turk” be rephrased to “to smoke like a Nepalese”. In all the countries I've visited so far I've never seen such dedicated, persistent, hardened smokers as the Nepalese.

When we stop at Bardiwas, a very sick woman comes aboard; she is being taken to hospital in Katmandu. The youths and men around her are chain smoking showing no regard at all for this poor woman who can hardly breathe. By the way, I'd like to suggest that the saying “to smoke like a Turk” be rephrased to “to smoke like a Nepalese”. In all the countries I've visited so far I've never seen such dedicated, persistent, hardened smokers as the Nepalese.It continues to pour with rain and I can't see anything through the bus windscreen. It suddenly dawns on me – this bus has no windscreen wipers! The bus carries on blindly through a wall of water. There seems to be nothing for it but to close my eyes and try to sleep to avoid further shocks. It's not long, however, before I can feel I'm being shaken by someone. Opening my eyes I see a man, looking and sounding upset, saying: “Foot down! Foot down!”.

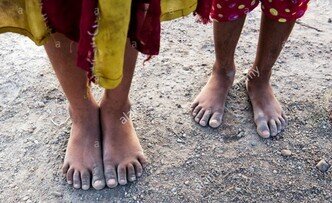

At first I can't quite understand what he's getting at, but then I realise that he wants me to move my feet which I had put up to rest them. In the Hindu religion feet are considered to be the most impure part of our body and therefore they are to be kept in a low position as far away from the head as possible. Religious taboos frequently coincide with rules of hygiene, or in any case with life conserving rules, but in this case the opposite was true. Anyhow, I do as asked and close my eyes again.

At first I can't quite understand what he's getting at, but then I realise that he wants me to move my feet which I had put up to rest them. In the Hindu religion feet are considered to be the most impure part of our body and therefore they are to be kept in a low position as far away from the head as possible. Religious taboos frequently coincide with rules of hygiene, or in any case with life conserving rules, but in this case the opposite was true. Anyhow, I do as asked and close my eyes again.But I am fated not to sleep. At one of our many stops a rather well-made woman gets on who, having pushed my luggage even further away, plonks herself down on me and on the passenger seated next to me. At first the whole thing seems just too absurd to be true; there's simply no room for a third person on these small seats and she can hardly expect to travel on our laps for the rest of the trip. I first attempt to make her understand this with a smile, but, when I see that she has no intention of moving, I push her away.

I'm usually kind to the Nepalese to the point of self-denial, but I can't stand arrogance either here or anywhere else. And in this case I don't even have any qualms about depriving a local of a seat. The bus is privately owned and there is a no-charge booking service. I wonder what kind of woman she is: she boarded the bus alone in the dead of night; she is talking, laughing and joking with the male passengers, in a country like Nepal where women do not go out and about alone, even in daylight and near home, and they would never dream of speaking to strangers, let alone men . . . . .

When she finally goes away I try to go to sleep again but the precipices I can make out just inches from the bus wheels are not inducive to relaxation.

Evidently, though, my final hour has yet to come since I arrive in Katmandu safe and sound. It's eleven o'clock and I've been travelling for eighteen hours. The sacks of cucumbers are unloaded; the fish, which has travelled with us hung out of the bus window, is delivered and its receiver sniffs it repeatedly before finally carrying it off; the sick woman, looking even more deadly pale, is helped into a cycle rickshaw.

And it is with these last images in my eyes that I go off in search of a three wheeler, happy for once to plunge into the traffic of the capital.

July 19th: Back in Katmandu

My grandfather always used to say: “There's no better sauce than hunger to make the food appetising!” I think this is exactly my case right now. I decide to go and have something to eat and drink at K.C. In fact, apart from the bones of the tandoori chicken and a little rice, I didn't have anything to eat at Janakpur.

At the table next to mine there's one of those tourists that begs the question: What on earth do these people come to Nepal for? Why don't they go and have a nice holiday in Switzerland?

At the table next to mine there's one of those tourists that begs the question: What on earth do these people come to Nepal for? Why don't they go and have a nice holiday in Switzerland?This one is French. For one thing K.C. is a restaurant tailor-made for tourists; in fact you see only tourists here. International cuisine, drinks in sealed bottles or cans, disinfected vegetables; in short nothing to complain about.

This French tourist starts by asking for a fruit juice and then when it arrives wants to know what make it is. The waiter obligingly brings the tin for her to see. She takes a look, shakes her head and sends it back, ordering some mineral water instead, but provided the bottle is well closed, for goodness' sake! The waiter returns with the mineral water. She feels the bottle: “But it's too cold!” The waiter, with admirable patience, takes this bottle back and returns with another at room temperature. She looks as though she is about to remark that this bottle is too warm but bites back her words only because the friend who is with her is clearly extremely embarrassed at this point. Then begins the 'window test' on the glass. Clearly the result leaves a lot to be desired regarding the cleanliness of the glass seeing that she picks up her napkin and starts rubbing the said object both inside and out with determined energy.

I have seen other tourists like her around here; they stay in Katmandu for their entire holiday or, at most, they venture as far as Pokhara in the tourist minibus. They get up around ten in the morning, breakfast in the restaurants of Thamel, then, all dressed up, wander around the shops looking for some exotic object to show off at home, or a bargain to boast about with friends. They leave Nepal with a very limited experience of the country, an experience which, furthermore, is misleading and false, and having caused harm more than anything else.

July 20th Quid Pro Quo

Walking around with my faithful companion, 'Lonely Planet Guide', looking for 'Mike's Breakfast'. In vain. No-one seems to know where it is. So I opt for the 'French Bakery', which is on the same street. This is an American style eatery, all green plastic and rock music blaring. The prices are rather steep but, well, I'm here hungry and thirsty . . . . .

Walking around with my faithful companion, 'Lonely Planet Guide', looking for 'Mike's Breakfast'. In vain. No-one seems to know where it is. So I opt for the 'French Bakery', which is on the same street. This is an American style eatery, all green plastic and rock music blaring. The prices are rather steep but, well, I'm here hungry and thirsty . . . . .What's more, I'm willing to go to any length to get away from the stink of the innumerable piles of rubbish.

Having ordered the usual pot of tea and the usual omelette, I decide to make a last attempt to locate the elusive restaurant by asking the waiter if he can help.  “Do you know where 'Mike's Breakfast' is?” I enquire. He looks very apologetic as he replies: “Sorry, madam, we only have these breakfasts”, pointing to the paper place mat on which there are pictures labelled 'Tom's breakfast', 'Jack's breakfast'.

“Do you know where 'Mike's Breakfast' is?” I enquire. He looks very apologetic as he replies: “Sorry, madam, we only have these breakfasts”, pointing to the paper place mat on which there are pictures labelled 'Tom's breakfast', 'Jack's breakfast'.

“Do you know where 'Mike's Breakfast' is?” I enquire. He looks very apologetic as he replies: “Sorry, madam, we only have these breakfasts”, pointing to the paper place mat on which there are pictures labelled 'Tom's breakfast', 'Jack's breakfast'.

“Do you know where 'Mike's Breakfast' is?” I enquire. He looks very apologetic as he replies: “Sorry, madam, we only have these breakfasts”, pointing to the paper place mat on which there are pictures labelled 'Tom's breakfast', 'Jack's breakfast'.What an incredible coincidence; the only time I've ever found breakfasts called by people's names.

July 21st

K.C. is closed today so I go to the restaurant opposite.  There I fall into conversation with a woman who is eating alone and who turns out to be English and Jewish – at least I deduce the latter from the Star of David pendant she's wearing round her neck. But over this there's another symbol I don't recognise and I ask her what it means.

There I fall into conversation with a woman who is eating alone and who turns out to be English and Jewish – at least I deduce the latter from the Star of David pendant she's wearing round her neck. But over this there's another symbol I don't recognise and I ask her what it means.

There I fall into conversation with a woman who is eating alone and who turns out to be English and Jewish – at least I deduce the latter from the Star of David pendant she's wearing round her neck. But over this there's another symbol I don't recognise and I ask her what it means.

There I fall into conversation with a woman who is eating alone and who turns out to be English and Jewish – at least I deduce the latter from the Star of David pendant she's wearing round her neck. But over this there's another symbol I don't recognise and I ask her what it means.She explains that it's the symbol of a movement for the freedom of lesbians. She goes on to say that right here in Katmandu she's discovered a Jewish Italian writer, Primo Levi, and has bought the English edition of his 'Se non ora, quando?' ['If Not Now, When?'] in one of the second-hand bookshops. I tell her that Levi was from Turin, my city, and that he committed suicide some years ago. As tears come to her eyes, I hastily change the subject.

July 22nd

The time has come to leave behind the relative luxury and comfort of Katmandu in order to go and share their 'uncomfortable' life with the Sherpas.

July 22nd - 23rd On the way to Shermatang

At ten o'clock, Laghkpa, Didi, Kelly and I leave for Banepa on a very old and run-down bus. Having stopped at Bhaktapur, which I know already, then Dhulikel, Panchal and Bahunpati, we arrive at Banepa a little before midday.

A quick lunch and then off again to Malemchi Pul. The road is horrendous, the bus is packed, we arrive exhausted.

To get back on our feet, so to speak, what better than launching at once on a steep climb in the driving rain? Thank goodness Kelly helps me to slow their pace, otherwise I'd never manage to keep up with the two Sherpas.

The scenery is splendid, but we never stop to admire it. What's more we are obliged to keep our eyes on the path, which is extremely slippery due to the rain, and take care where we put our feet. My heart is bursting, I'm gasping for breath, but nevertheless my pride won't allow me to give in.

After an exhausting four hour relentless climb, with not a moment's pause, we stop at a small shop which has a room with two straw mattresses in it. It is here we spend the night.

After an exhausting four hour relentless climb, with not a moment's pause, we stop at a small shop which has a room with two straw mattresses in it. It is here we spend the night.  By now it is dark and a thick mist has come down. We are soaked to the skin and in need of a good fire to dry us out.

By now it is dark and a thick mist has come down. We are soaked to the skin and in need of a good fire to dry us out.Unfortunately the stove in the kitchen gives out more smoke than heat. So, after a supper that I can't manage to eat, we take off our wet clothes and hang them out before crawling under the quilt.

My whole body tingles, but I decide to ignore it and try to sleep. Sleep doesn't come. I peep out of the windows anxiously awaiting the first sign of dawn. As soon as I see a glimmer of light, I get up in the hope of beating the others to be able to have a proper wash instead of the usual 'face-only' one.  What a vain hope: the family whose guests we are is already up and about and there are already people setting off down the valley.

What a vain hope: the family whose guests we are is already up and about and there are already people setting off down the valley.

What a vain hope: the family whose guests we are is already up and about and there are already people setting off down the valley.

What a vain hope: the family whose guests we are is already up and about and there are already people setting off down the valley.I collect my clothes that I had hung out on the verandah last night hoping that they would somehow dry. They are dripping. I get into them all the same and go down for some tea.

The mist is really thick and the humidity very high. Coming to the Himalayas at this time of the year calls for an iron will and constitution!

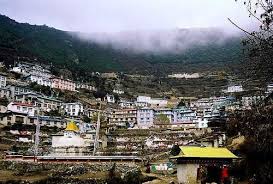

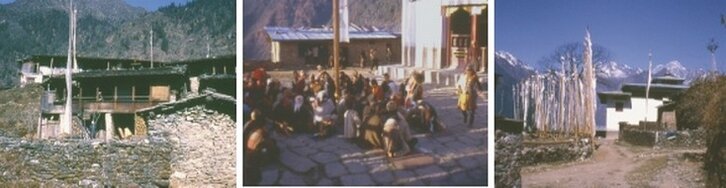

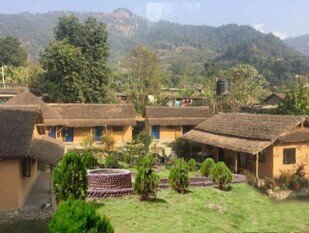

We set out again around ten, the rain having replaced the mist. About three hours later we reach Shermatang and Laghkpa's house where we find his aunt who is a Buddhist nun.

The house consists of a ground floor store room and a single room on a mezzanine floor. The furniture is basic: two beds, a dresser and a small stove. Prior to the family moving to Katmandu, twelve people lived in this one room.

We are offered Tibetan tea while the potatoes are cooking. Perhaps because the firewood is damp, or perhaps because the stove has an inefficient flue and there's little draught, the atmosphere is so smoky that it makes the eyes burn.

In no time at all news gets around in the village that Laghkpa, Didi and two foreigners have arrived and everyone, friends and relatives, come to say hello.

Kelly and I take it in turns to go to the spring and draw water for the tea and to wash the cups and plates. At the rate of today's visits, this soon becomes a full-time job.

These Sherpas, distant cousins of those more authentic ones of Solu Kumbu, are cheerful and talkative: despite the language barrier, they manage to involve us in the conversation and fire all sorts of questions at us. By seven o'clock it's already dark and we eat rice and lentils by the light of a small candle. Towards ten we retire. Tomorrow we have an early start.

FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF THE HELAMBU SHERPAS

(they call themselves Sherpas, but really they are Bhotiyas)

In a film I saw some time ago, the teacher in an American college suggested to his students that they should always have an original and different point of view when facing reality.

The Sherpas show this kind of originality in their use of the tools and gadgets of everyday life. Here are just a few examples:

they use a piece of wood chewed at one end to clean their teeth, while their toothbrushes are kept for cleaning and shining the pots and pans; the sponge for washing the dishes is used to clean the red clay floor; the aforesaid floor is ideal for sleeping on, while the bed can be used to rest clothes and sundry other items on; the floor cloths are, for them, a perfect cushion, while the cushion makes a very good stopper for the cracks and the window openings – there's no glass in the windows, just the wooden framework – during the colder months . . . and so forth!

July 24 th Tarke Gyiang

Awake at 5 a.m. Outside all is dark and foggy.

Awake at 5 a.m. Outside all is dark and foggy.We drink two cups of tea, eat two boiled potatoes and are off to the vegetable patch to dig up some more.

When you read in guide books that the core ingredient of the Sherpas' diet is the potato, you don't really realise just how literally true this is!

Our duty done, we set off for Tarke Gyiang, a large village at 2,747 metres above sea level and the seat of a Buddhist temple and monastery.